When you're creating something, especially when you're a person who obsessively appreciates quality, it's really easy to try to do it "right" on the first try (some people may call this perfectionism). This is a noble goal, but is very dangerous because it can easily cause a project to grind to a halt while you attempt to polish small details.

In the context of software engineering, this is extremely prevalent. When you begin developing software, you know no best practices. This means you tend to produce a lot of incredible spaghetti code. As you grow you learn that a little work up front to write your code in a clean way can actually save you time when you need to go back and change/extend it. This is the whole mentality behind Robert C. Martin's book Clean Code . This book is notoriously polarizing, but has a lot of really good wisdom in it. Unfortunately it doesn't hit enough on how to protect yourself from the trap of of taking this mentality to its logical extreme - Prematurely over-engineering.

It's really easy to accidentally fall into the idea that the more time spent polishing your code, the better it'll be for solving your problem... before you have even made it do the thing you want to do. This idea does not invalidate the mindset that Clean Code conveys. A spaghetti code-base which deadlocks your project is just as useless as a perfect one which never gets finished. Thus, as with all things, this is an optimization problem to find a happy middle-ground. Finding this is not a perfect science because measuring how "good" code is is surprisingly difficult. And it also varies per person due to different skill levels in software engineering and different levels of proficiency with the tools/libraries a certain project requires. But the general rule of thumb that I follow is that a maker should do the things that:

Some examples for people of increasing levels of proficiency:

Say you have a lot of logic coupled with a lot of data and it's becoming more than initially expected. A simple refactor is to pull that data into some kind of encapsulation. I'll give the example of a class, but I understand that object oriented design is polarizing. This suggestion has two major benefits (Again not groundbreaking. These are big benefits people tout about OOP):

Note that this is NOT the time to consider making your class perfectly extensible with the perfect API and perfect encapsulation. If there are any changes which meet the above bullet points and do get you closer, you should do them. But if coming up with those changes is not immediately natural that's an indicator of a trap. Just start by literally dragging all of the coupled variables and functions into your encapsulation construct of choice.

Say you are only making one component of a project which requires many more components and you find that interfacing with it is either convoluted or it has a lot of parts to the interface which are never used. This is a really good place to consider what the interface of this component really needs to be. What is its purpose in the greater project? ONLY implement what's required for that. The common trap here is to try and make this component extremely reusable so you make APIs extremely generic or you add APIs for things your program won't ever use. Every developer feels the pull of wanting to expand their toolbox of reusable code for future projects... but in the pursuit of preparing code for the toolbox you can forget that the code has a job now . Make it good for that job. Then if you need it somewhere else, that is when you can think about how to make it better.

As you can see from these examples, it's a very case-by-case kind of thing. It's part of the responsibility of a maker to be constantly considering whether a change gets them closer to a finished project or a dead-end. And as the maker gets more experience, their internal compass for making those decisions gets more refined.

This brings me to a maker mentality that I call "The Second Try". The gist is this:

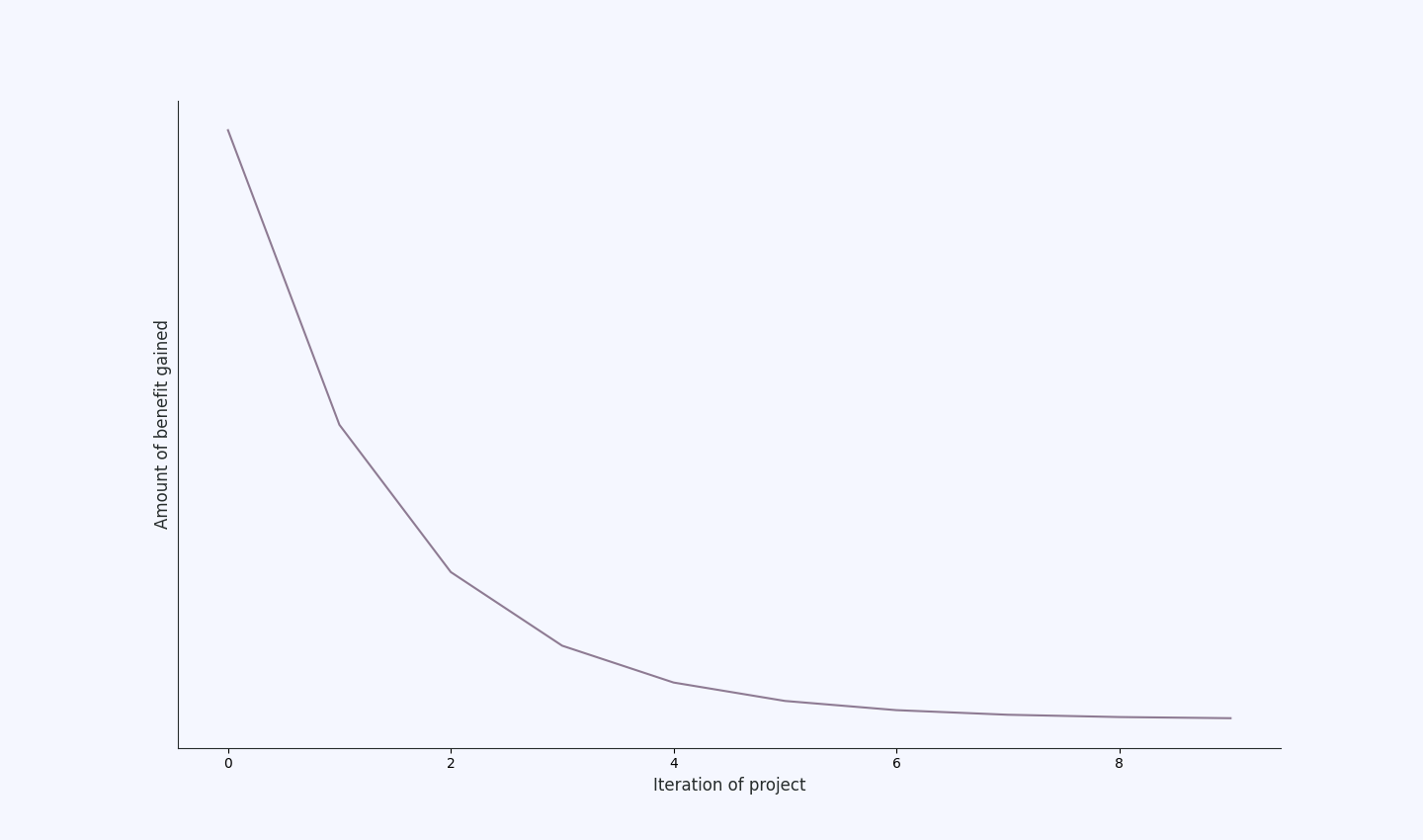

As mentioned above, this requires that balancing act / internal compass to make sure you don't shoot yourself in the foot with a codebase which can't be finished or with a half-finished pristine codebase which burns you out on the project you wanted to do. But the insight which leads to this mentality is that doing a project multiple times generally has monotonically diminishing returns on how much benefit you get. Thus, by definition, the second iteration of the project is the one which gives the most benefit compared to future iterations.

For example, consider you followed the advice above and managed to do the exact minimal amount of work required to make your project. Naturally, this means a lot of places are going to be not very reusable or extensible. Perhaps there's even a bit of pasta in there. You now know exactly what functionality is necessary for your project. You don't have to solve that problem any more. You can start to think about how to make it better. Maybe you wanna add more features. Maybe you wanna clean it up and publish it to the world so others can make it or extend it. Now you can just focus on doing that.

The way that I like to start this process of the second try is by simply throwing away the whole prototype. That is to say - pretend you had this knowledge of what's necessary but had no implementation and begin implementing it again. You'll pretty quickly start thinking about how you did things last time. You'll think about what pitfalls that solution might have. You might find that some parts of the project actually ended up good enough to be brought into this new version and some might need a total re-think. This is your opportunity to think about those things and solve those problems. This is the benefit of this mentality. The first time through you're just solving the problem of "How do I bring this thing into the real world" and the second time through you're just solving the problem of "How do I make this thing better".

Following through this process you'll eventually land on a new version of your project (in my experience, in a faster amount of time than the first try). After this, I switch into maintenance mode. This is where ideas from clean code come in. Ideas like minor, local refactors and iterative improvement. It's generally not beneficial to re-architect the whole project again so you should focus on fixing little problems as they come up.

There is a pitfall with this idea. That is it's really easy to see your prototype and take too much from it. This comes from the conflation that code that solved the "How do I bring this thing into the real world" problem is the same as code that solves the "How do I make this thing better". It is again the responsibility of a maker to remind themselves that these things are different. Not everything you wrote the first time is reusable. That's okay.